The Body-as-Machine is Dead - We Have Killed it

Where to next?

God is dead. God remains dead. And we have killed him. How shall we comfort ourselves, the murderers of all murderers? - Friedrich Nietzsche 1

“God is dead” remains one of the most famous quotes from the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche1. Nietzsche, being the atheist that he was, didn’t mean that people had literally killed the God he believed in. Rather, he meant that in the wake of the Enlightenment, Western society was transforming in such a way that the idea of God had begun to die and was being replaced. European society no longer needed a transcendent God as the universal source for all morality, value, or order in the universe; philosophy and science were capable of doing that for them.

God, in this instance, should not simply be dismissed as an illusion or false perception, as so many atheists often do. It might be true that God was not a man floating in the sky, but God was real insofar as God played a significant role in shaping the Western world. God was an extraodinarily potent thing - an assemblage - organzing and assembling material in the world. Without God, entire empires, societies, cities, and cultures would not have existed. However, with the Enlightenment, new concepts (or assemblages) were taking God’s place.

Nietzsche was a prudent analyst, noticing this societal trend in the 1880’s when Europe was still incredibly religious. “God is dead” for Nietzsche was a statement of fact; he accurately recognized that Christianity was in decline due to no longer being a coherent belief system that organized society. It was also a statement of warning about what the future holds, what might replace Christianity, and what new issues might unfurl.

Similar to Nietzsche’s sentiment, I think it is quite evident that the biomechanical understanding of the body-as-machine in physiotherapy is dead. While it has been an incredibly powerful concept, physiotherapy no longer needs it; the profession has moved on. But, what has replaced it? Before we get into that, let us first remind ourselves what exactly the body-as-machine is and where it came from.

The-Body-as-Machine

There is no doubt that the concept of the body-as-machine played a pivotal role in legitimizing physiotherapy as a provider of rehabilitation services and shaped the profession’s identity2.

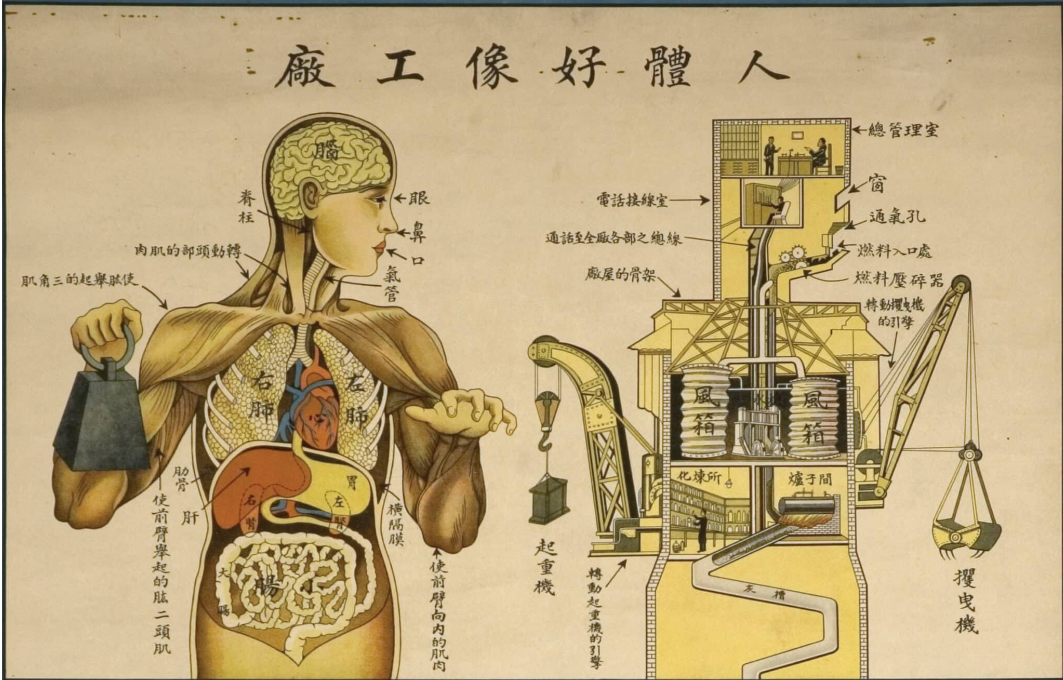

Implicit in the assumptions of the body-as-machine is the notion that bodies are made up of mechanical parts, mimicking the machines of the industrial revolution234. Like a mechanical machine, body parts ‘wear out’ with use - especially when different parts are ‘misaligned’ from the corporeal norm - which then require repairing or fixing by an ‘expert’ clinician.

Many have rightly argued that the concept of the body-as-machine was disciplinary, and had emerged from what Michel Foucault calls a ‘disciplinary society’5. To oversimplify the issue, this means the body-as-machine would use a binary of normal/abnormal to discipline bodies to adhere to an “Ideal” norm, where the norm was deemed the most healthy6. This could include normal posture, normal range of motion, normal muscle function, normal gait7.

Professor David Nicholls has done an excellent job at tracing this history, writing that “[t]he body-as-machine became a powerful [concept], particularly after the Industrial Revolution, when it was thought that it might apply not only to the function of various bodies, but to the machinery of production that had become necessary to fuel the growth of an economy.”2

Therefore, conceptualizing the body as a mechanical machine not only disciplined bodies to adhere to an ‘Ideal norm,’ but also enabled nation states to effectively govern their growing populations, their individual freedoms, labour, and health while also simultaneously fueling the industrial capitalist machine23. After all, the healthier a population, the more economically productive and valuable they are. For example, during and after World War 1, physiotherapy became integral in recapacitating debilitated and disposable surplus populations to the machinery of economic production, making them valuable again - either by returning injured soldiers to the frontlines of various wars as biological fodder for the globalization and expansion of Euro-American empire, or by returning bodies to work, to physically labor in factories so the nation state could meet the demands of the rapidly expanding global market238. Bodies that cannot labor are surplus – a drain on the nation8. Physiotherapy and the body-as-machine was (and arguably still is) instrumentalized to manage populations, their health, and physical ability, for the sake of nation-states, functioning as a conduit of societal and political power2.

Physiotherapist ‘expertise’ in disciplining, normalizing, and ‘correcting’ the ‘broken’ or pathological' body, and producing ‘healthy,’ disciplined bodies, was instrumental in helping physiotherapy gain social, and political legitimacy in the lead up to World War 1, significantly shaping the profession’s identity2348. Understandably, then, the concept is one which physiotherapists find very hard to part with. Today, however, literature retrospectively scrutinizing the profession’s biomechanical past and the harms it has caused is increasing, making it easier than ever to justify abandoning it.

Some scholars have highlighted that the assumption of the body as fragile and in need of ‘Ideal’ alignment and functioning to be healthy causes worse health outcomes91011. Others argue that the reductionist search for ‘objective’ lesions or abnormalities has rendered the subject and their ‘lived’ experience an unwanted appendage to the physical lesion under investigation1213. Furthermore, the corporeal norm has long been criticized for its European humanist, hetero-patriarchal, and ableist presuppositions that render those that do not fit this norm undesirable and pathological2714. And, of course, there exists no shortage of online discourse on the matter with many popular physiotherapists insisting “the body is not a machine!”

However, like God, we should not assume that we were disillusioned by the body-as-machine and that we now ‘better’ understand how bodies work (although this is true in part). Rather, we should understand the body-as-machine as a real thing which played a crucial role in shaping physiotherapy on a material level. It assembled the kinds of instruments, interventions, words, and behaviours physiotherapists would adopt. Today, however, a different assemblage has, or is in the process of, replacing the body-as-machine.

A New Era

Just as the age of enlightenment and its principles of rationalism and scientific knowledge replaced God as a measure of Truth, if you read the works of Gilles Deleuze15, Jasbir Puar16, Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri17, and even Michel Foucault18 you would be quick to notice that they argue that disciplinary societies (from which the body-as-machine emerged) is being replaced. Similarly, we are quite obviously no longer gripped by industrial capitalism. We have moved on to what some have called late-stage capitalism, neoliberal capitalism, surveillance capitalism, algorithmic capitalism, or some version thereof.

If the body-as-machine arose from a disciplinary society and industrial capitalism, what concept of the body does physiotherapy currently operate with in our current society and political economy? How is our concept of the body changing? What alternatives are replacing the body-as-machine?

If the body-as-machine mimicked the simple machines of the industrial revolution, does the new concept of the body mimic today’s machines such as computers, the internet, and artificial intelligence - modulation machines?17

If clinicians who deploy the body-as-machine could be heard saying things like “your joints wear and tear,” “your back pain is likely due to poor joint alignment and poor posture,” and “muscle imbalance is causing muscle pain," then what are clinicians saying today? What discourses are gaining popularity and what ends are these discourses serving?19 And if the body-as-machine served state and corporate interests during the industrial era, might these new discourse be serving similar ends just in a contemporary neoliberal socio-political climate?

It has become overwhelmingly clear to me over the last few years that those who (rightfully) criticize the body-as-machine propose instead some version of a holistic person-centred, biopsychosocial, embodied, lived alternative - one that replaces the clinician as the authority and expert with the patient as the authority and expert of their own body. Might this be a symptom of the passage from the body-as-machine to a new concept of the body - one that also serves corporate and state interests, just in new ways?

For those who contend that “This is not like the body-as-machine. This has proven to improve the lives of our patients. Plus how bad can being holistic and person-centred be?” I would like to remind you that missionaries had nothing but good intentions for those whom they ‘saved.’ Similarly, our biomechanical forefathers (and mothers) had nothing but ‘good intentions’ for those who they ‘fixed,’ believing themselves to be serving their society and helping people regain their health.

It is my opinion that we are currently, willfully and enthusiastically, plummeting into the same well-intentioned abyss, where presumed benevolence cloaks the larger socio-political systems we and our profession are serving.

Is it not our responsibility to avoid the mistakes of our predecessors and be “harsh and deceptive to what [we] love?”20. To pay attention to, and scrutinize, what presents itself as common sense? “It’s up to [us] to discover what [we’re] being made to serve, just as [our] elders discovered, not without difficulty, the telos of the disciplines”15. I wonder if we’ll look back in a few years and scrutinize the new concept of the body - maybe we’ll call it the body-as-modulation1516.

References

-

Nietzsche FW. The gay science. Kaufmann W, editor. Random House; 1974. ↩︎

-

Nicholls DA. The end of physiotherapy. London (GB): Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group; 2017. ↩︎

-

Nicholls DA. Physiotherapy otherwise. Auckland (NZ): Tuwhera Open Access Books; 2021. ↩︎

-

Nicholls DA, Gibson B. The body and physiotherapy. Physiother Theory Pract. 2010;26(8):497–509. ↩︎

-

Foucault M. Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison. Sheridan A, translator. New York (NY): Vintage Books; 1995. ↩︎

-

Praestegaard J, Gard G, Glasdam S. Physiotherapy as a disciplinary institution in modern society - a Foucauldian perspective on physiotherapy in Danish private practice. Physiother Theory Pract. 2015;31(1):17-28. ↩︎

-

Breedt E, Barlott T. Physiotherapy’s necessity for ableism: reifying normal through difference. Disability & Society. 2024;1–24. ↩︎

-

Adler-Bolton B, Vierkant A. Health communism: a surplus manifesto. Verso; 2022. ↩︎

-

Caneiro JP, Bunzli S, O’Sullivan P. Beliefs about the body and pain: The critical role in musculoskeletal pain management. Braz J Phys Ther. 2021;25(1):17 29. ↩︎

-

Darlow B. 2016. Beliefs about Back Pain: The Confluence of Client, Clinician and Community. International Journal of Osteopathic Medicine 2016;20:53–61. ↩︎

-

Darlow B, Dowell A, Baxter GD, Mathieson F, Perry M, Dean S. The Enduring Impact of What Clinicians Say to People With Low Back Pain. The Annals of Family Medicine 2013;11(6):527–34. ↩︎

-

Sviland R, Martinsen K, Råheim M. To be held and to hold one’s own: Narratives of embodied transformation in the treatment of long-lasting musculoskeletal problems. Med Health Care Philos. 2014;17(4):609–24. ↩︎

-

Thornquist E. Face-to-face and hands-on: assumptions and assessments in the physiotherapy clinic. Med Anthropol. 2006;25(1):65–97. ↩︎

-

Gibson BE. Disability, connectivity and transgressing the autonomous body. J Med Humanit. 2006;27(3):187–96. ↩︎

-

Deleuze G. Postscript on the societies of control. October. 1992;59:3–7. ↩︎

-

Puar JK. The right to maim: Debility, capacity, disability. Durham (NC): Duke University Press; 2017. ↩︎

-

Hardt, Michael, and Antonio Negri. 2000. Empire. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ↩︎

-

Foucault M. “Society Must Be Defended”: Lectures at the College de France, 1975–1976. New York (NY): Picador; 2003. ↩︎

-

Tichenor E. What Can Borderline Do? Essays on Madness, (De)Pathologization, & Empire (MSc thesis, University of Alberta) 2014. ↩︎

-

Deleuze G. Proust and signs: The complete text. 1st ed. Minneapolis (MN): University of Minnesota Press; 2004. ↩︎