Sublime

How do we go on when we no longer know?

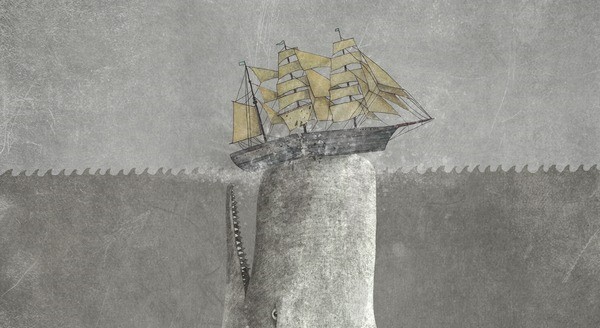

For the most part, in this tropic whaling life, a sublime uneventfulness invests you — Herman Melville

One of my greatest fears has always been the ocean and one of my greatest fascinations has been with whales.

My mind recoils at something so immeasurably more powerful than me, whose weight, force, scale could crush me without the remotest hope of me being able to resist it. I could stand for hours watching the waves ruffle. When you try to focus your view, the ocean laughs at your tininess; it is too big for us. The ocean pushes us to the limits of our ability to capture and tame, leaving us vacant.

The whale punctuates the mystery of the ocean with its paradoxical existence. Its enormity elegantly glides across the ocean stage, dancing and singing its sad songs. The whale is entangled in the ocean myth, becoming wrapped up in its darkness, disappearing into its belly. Its imposing presence is imposed upon, swallowed up by the ocean. When the whale appears - the ocean becomes more mysterious. In my faculties the whale is a superposition, both finite and infinite. Both a wave of overwhelm and a mere particle in the ocean. Its incomprehensible presence brings about my own reckoning with my finitude and yet it itself is comfortably contained by something even greater, bringing to bear the whale’s own finitude. How can a creature be both imposing and elusive?

Like the hum of a fridge in the kitchen or the crackle of the radio static, our unconscious minds have got used to the constant droning question “how can we be both significant and insignificant”. For me the ocean teases the questions to the surface bringing with it the feeling of being not apart from the world but being a part of the world, fully material and fully alive.

I don’t think I am unique in my fear and fascination with the ocean. As children, we are almost universally afraid of the dark, the unknown, the concealed. Horror films monopolise on this, often placing hidden figures in dark scenes rife with unpredictability in order to evoke something primordial in us.

We seem to crave predictability; perhaps being able to predict the future has been evolutionarily beneficial. Those who predict danger survive and pass their genes on. Those who wait to confirm that what they are seeing is in fact a predator are too late.

There are times where we are thrust into the depth of the ocean, when we encounter the unknown, the unpredictable. We solve this uncertainty with certainty, fear and anger. We become extreme versions of ourselves. We entrench ourselves in what we are familiar with. If we are politically conservative, we become more conservative. If we are liberal, we become more liberal.

The trouble is that Being (what there is) is essentially in motion. Being isn’t being at all, but is becoming. This creates tension between our need for predictability and the innate emergent nature of the world. If we are to move and adapt with the world we need to adopt not a sedentary outlook, but an epistemologically flexible posture - one of mobility. That is to make room for epistemic deterritorialization and reterritorialization. If we are to move from one cavern into the next, we do not simply transport ourselves, we have to navigate through the space between the caverns. To move from A to B, we have to go from A to not A. We do not go from certainty to certainty, but from certainty to uncertainty, from stability to instability. We let go of what we recognize, step outside of our categories.

How do we move towards the space which our human nature has been designed to avoid? Strikingly, we have been provided with a solution, one which transforms fear into awe. This is what we will call the sublime.

Philosopher Emmanuel Kant would say we should not confuse the sublime with beauty. Beauty is where our categories are aligned, in harmony, everything seems to come together, each part complimenting the other. We have a feeling of peace and concordance.

The sublime, in contrast, is an experience of discordance, when things don’t seem to fit. We are presented with something which we cannot process through our established concepts and so we are forced outside of our concepts. The sublime is the encounter we can’t account for. It exceeds the boundaries of our comprehension. It is characterised by the sensation that there is more than what is presented to us.

It (the sublime) is a feeling which he would like to call a sensation of ‘eternity’, a feeling as of something limitless, unbounded—as it were, ‘oceanic’. It is the source of the religious energy which is seized upon by the various Churches and religious systems — Sigmund Freud

At the moment of the sublime encounter, the sublime subtracts; it cuts out everything that we recognize. It subtracts all constants, stable or stabilised concepts. Philosopher Jean-François Lyotard says what we are witnessing is the differend; the straining of the mind at the edges of itself and at the edges of its conceptuality. It is an experience which tears the subject from itself, often leaving us without words.

Take a baby for example. When watching a baby interact with the world it is in a chronic state of awe, submerged in newness. The sublime is all around and categories need to be created to account for what is being experienced. At this point we, who have cut up the world with our tongues, feed it to them in the same way that it was done for us.

This is what we do, we paint the world with words, we draw lines between things and create concepts to project meaning onto the world. To define is to confine. It constricts the virtual creativity of experience. When we encounter the sublime, concepts to describe this feeling are lacking, for it is the deficiency of conceptuality itself that we experience. Lyotard describes this as, “the unstable state and instant of language wherein something which must be able to be put into phrases cannot yet be.” We might say that this reveals the fact that there is more to life than that which we are able to perceive within the horizon or context of our own subjectivity.

Lyotard argues that Auschwitz offers something that is unpresentable in the presentation of history itself, a horror so infinite that a “silence” is “imposed on knowledge”. To represent it is to misrepresent it, and hence any regime is going to leave this powerful silence always on the edge of any discourse about it.

As Elaine Scarry (1985) has demonstrated, in many ways pain “resists language” or “actively destroys it, bringing about an immediate reversion to a state anterior to language, to the sounds and cries a human being makes before language is learned.” As a result, those in pain are constrained to express their pain using metaphor, often creatively. This is what John Quintner refers to as encountering the aporia of pain. It is unlikely that pain can ever be apprehended objectively (to be seen as an observable “thing”). In the clinical encounter, the clinician’s experience becomes one of uncertainty, discomfort and doubt, much like the sublime encounter.

Herman Melville’s Moby Dick is sublime because of its terrifying enormous existence. So is the ocean itself. Standing at the foot of a mountain might evoke the same feeling of awe as watching a tornado tear through a town. It is an experience of “too much”. We are presented with the sensation of moreness. There is more happening than what we can account for.

According to Deleuze, behind our constructs there is something we can sense which we cannot bring into recognition or experience directly. We sense something which is beyond what is presented to us. Deleuze would say what we are palpating is difference, or “difference in itself”. It is the creative force which produces what appears to us.

In a theatre thus purged of all actuality and representation, only creation as such will act. ‘Everything Remains, but under a new light.’ Anything can emerge, but only as the ‘sudden emergence of a creative variation, unexpected, sub-representational — Peter Hallward

The sublime encounter is an opportunity to allow new ways of thinking outside of our current conceptual frameworks to emerge. Every lived experience is rich with new perspectives, thus, every clinical encounter with someone in pain is an opportunity to defamiliarize ourselves and step into a new world. Yet more often than not, we miss this opportunity and opt instead to retreat to the comforts of what we already know. In the clinical encounter I might project my biases onto the person in pain, caricaturing them as, “the difficult client”, or “a catastrophizer” for example. Drawing connections between them and other people I may have encountered, seeing patterns where there are none, thus categorizing them unjustly. Perhaps we tend to shrink back to what we are familiar with because it simplifies our experience of the world and demands less of us. What if, in the clinical encounter, we asked ourselves “who do you remind me of?” instead?

To Gilles Deleuze, “the dogmatic image of thought” is the kind of thought which occurs when we encounter something that takes us beyond recognition, into the unknown, and reflexively we try to bring it back into recognition. We discipline it into our old categories. We speak without thought. In healthcare we capture it with words which are colonised by science and certainty.

Man has to awaken to wonder — and so perhaps do peoples. Science is a way of sending him to sleep again — Ludwig Wittgenstein

Crucially, real “thought” is when we encounter something that takes us beyond recognition and we allow new creative possibilities to emerge, resisting codification. To Deleuze “thought” is knowing what no one else knows, actively engaging with the sublime, allowing the dissonance to shake the walls of our old concepts and creating other ways of knowing.

The larger the island of knowledge, the longer the shoreline of wonder — Ralph Sockman

To wonder is to wander. Much like the baby, we need to see with new eyes and be born again. We must be curious like a child, ask about the world, let it envelop us and pull us offshore and out to sea. When we are thrust to the fringe of what we know, instead of scrambling back, what if we peered over the edge? I wonder what falling feels like… Is it frightening? Or might it be liberating?

Let me fall if I must fall. The one I will become will catch me — Baal Shem Tov

Recommended Reading:

Loose, D., 2012. The sublime and its teleology. Leiden: Brill, pp.205-222.

Hallward, P., 2006. Out of this world: Deleuze and the Philosophy of Creation. London: Verso Books.